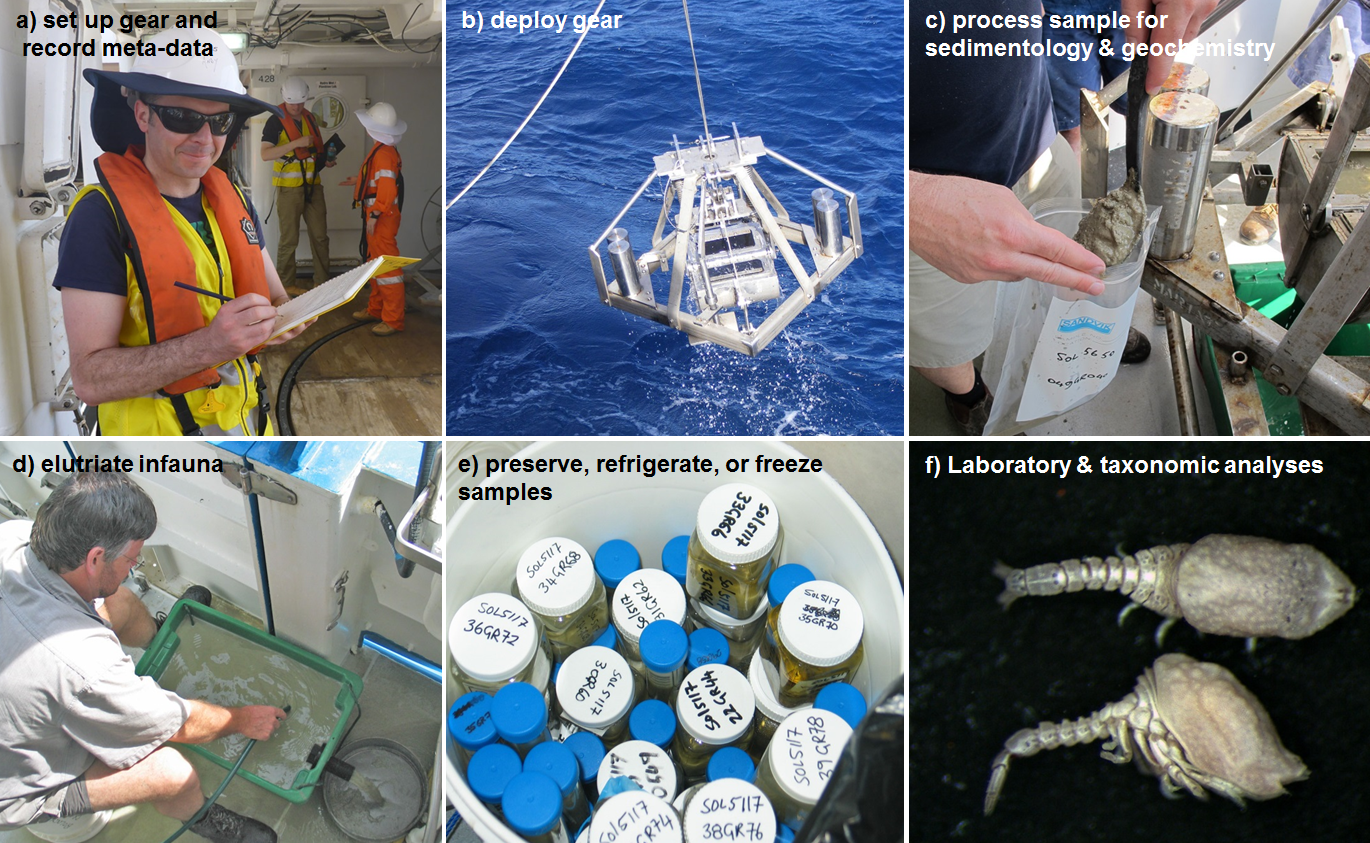

A visual summary of some of the key steps to follow when deploying grabs or box corers is shown in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1: Images from key steps involved in the use of grabs or box cores for marine monitoring: a) Recording metadata during gear deployment, b) Retrieving a Smith-McIntyre grab, c) Transferring sample for sedimentological analysis from grab to storage bag, d) Elutriating sediment over a sieve, e) Preserving a bucket of infaunal samples in ethanol, f) Sorting cumaceans under the microscope from elutriated infaunal samples.

Onboard sample acquisition

- Use multibeam data or underwater imagery to confirm appropriate areas to sample (soft vs hard substrate) and to identify the most appropriate equipment based on fine or coarse sediments.

- Use USBL System to ensure accurate positioning (Schlacher et al. 2007, Williams et al. 2015) [recommended, especially in deep waters]

- Document the specifications of all sampling gear to be used. This includes gear size and configuration (dimensions, weight) and deployment needs (wire length estimated, USBL methods), as well as sampling surface area, maximum volume, and maximum digging depth. This information must be included in survey metadata.

- Record all metadata related to each sample station, specified in Table 9.2.

- Deploy the grab or corer according to gear-specific protocols. Record GPS position, date, time and water depth when the sampler reaches the sea bed.

- When the equipment is lifted from the water, follow gear-specific protocols for its safe return to deck and access to the sample. Special care may be needed in rough conditions to ensure the sample is not spilled or in situations when the grab or corer has not been triggered.

- Assess the success of deployment and record the proportion of grab or corer filled (Table 9.2).

- If there is significant damage to gear, gear closure failure, sample spillage or scant sample return, the sample should not be used in quantitative comparisons with other deployments. If possible, repeat a deployment at that location. Scant sample is defined as being at least 50% empty.

- Record general observations, particularly conspicuous biota, general sediment description, and evidence of anoxic or reduced sediments (i.e. black/green colour, sulphur smell).

- Photograph the entire sample with the station identification placard. If taking photos of individual biota from the sample (must be done after step 10), photograph them on the station identification placard. It may be worth considering including a basic scale bar on station identification placards for this purpose.

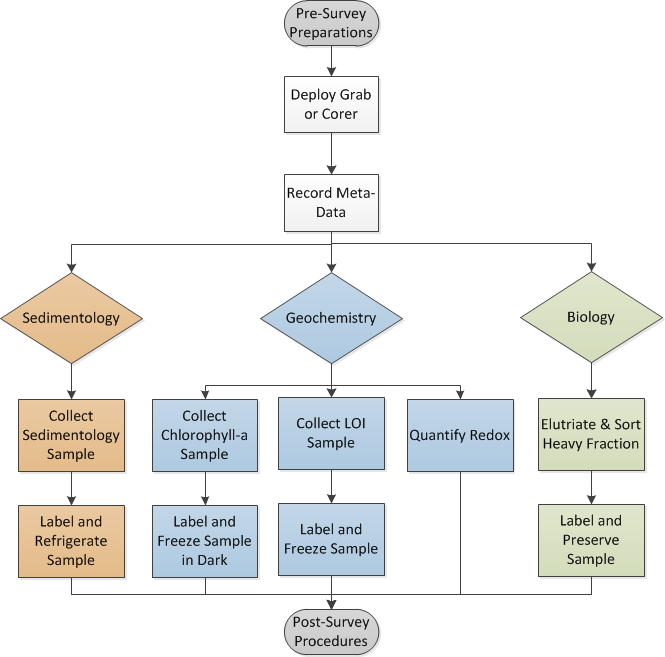

- As soon as practical, begin onboard processing of the sample for sedimentology, biology, and biogeochemistry (next sections, Figure 9.2).

- After all samples have been removed (next sections, Figure 9.2), thoroughly wash gear to prevent cross-contamination. Set up gear for next deployment or safely secure for long transits or if operations have ceased for the day.

Figure 9.2: Workflow for onboard sample acquisition and processing from grabs and box cores.

Table 9.2: Sample field datasheet to record metadata from each grab or corer deployment. Waterproof paper and pen/pencil is required.

Onboard sample processing & storage

- For most equipment, the sedimentology and geochemical sub-samples can be accessed while the sample remains in the grab or corer, thus minimising disturbance. The biological sub-sample can be processed after these sub-samples have been removed.

- When processing biological samples, pass any excess water from the sampling gear over the sieve; for a box core this will likely need to be done with a siphon. Process the material retained on the sieve (refer to biological steps below).

- Undertake geochemical, sedimentological, and biological processing steps below for each sediment sample collected.

- After samples are processed, transcribe the metadata from Table 9.2 into digital format. This can be done in the evening or during other shipboard operations, but it should be done onboard because it provides an immediate back-up, allows for correction of obvious errors, and facilitates timely metadata release.

- During demobilisation, ensure samples and drums are properly closed and implement shipping according to decisions made during pre-survey planning.

Sedimentology (texture, colour and composition)

The following procedures are to be used to obtain sediment samples for quantification of commonly analysed metrics related to grain size and carbonate content (Nichol et al. 2013).

a) Using a spatula or spoon, scrape surface sediment, collect a maximum 300 g wet weight (~2-4 tablespoons) in a plastic zip-lock bag. If you’re collecting a particle size sample for comparison with contaminants data or for integration in the national seabed sediments collection, this must be taken from the top 2 cm of the sample. If you’re collecting a particle size sample for comparison with infaunal data, then the particle size sample should be representative of the whole sample profile. If you are sub-sampling a grab sample for sedimentology, biogeochemistry, and biology, leave any visible living organisms for biological steps below, but retain shell material.

b) Describe the entire sediment sample using a visual assessment. First identify whether the dominant constituent is Mud, Sand or Gravel. Gravel is > 2 mm diameter, including any shell fragments, coral, rhodoliths or rocks. Sand is < 2 mm and > 0.063 mm diameter. Mud is < 0.063 mm diameter.

The following description will assist a visual and tactile assessment:

- Sand – Individual grains can be readily seen and felt. When wet, sand will form a cast that crumbles when touched.

- Muddy sand – Sand grains are visible but the sample contains enough mud (silt and clay) to make it somewhat cohesive. Will form a cast when moist that can bear careful handling without breaking.

- Mixed sediments – Mixture of sand and mud. Has a gritty feel, but smooth overall and slightly plastic. Will form a cast when moist that can bear firm handling without breaking.

- Sandy mud – Overall fine texture, slightly gritty to feel that can form a thin ribbon when rolled between fingers. Will form a cast when moist that can bear robust handling without breaking.

- Mud – Uniformly fine texture, sticky and with very slight gritty feel if silt is present. Will form a long flexible ribbon when rolled.

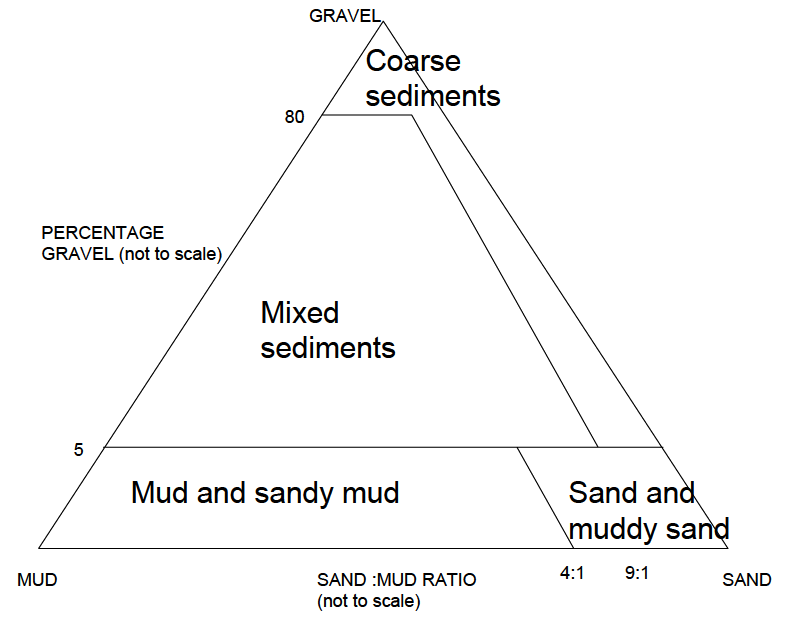

c) Assign a Simplified Folk Textural Class to the sample, based on the estimated mud, sand, and gravel proportions (e.g. Figure 9.3, Table 9.3).

Figure 9.3: Simplified Folk Textural classes

Table 9.3: Simplified Modified Folk Textural classes for visual classification of seabed sediments

| % Gravel | Sand : Mud Ratio | Simplified Folk Class |

|---|---|---|

| >80 | >9:1 | Coarse sediment |

| >5, <80 | <9:1 | Mixed sediments |

| <5 | >4:1 | Sand and muddy sand |

| <5 | <4:1 | Mud and sandy mud |

d) Assign a colour to the whole sample using a Munsell colour chart, noting the Munsell code (colour, value, chroma) and colour name [Recommended].

e) Estimate whether the sample is comprised of mostly (>50%) carbonate material, non-carbonate (i.e. lithics), or mixed.

f) Note the presence of other materials, such as whole shells, articulated bivalves, shell fragments, corals, wood or lithics and record the relative abundance as: Trace (just noticeable); Few (noticeable); Common (very noticeable); Abundant (little else noticeable).

Record the above properties with all available metadata (Table 9.2), as in the example below:

- Sand and muddy sand

- 7.5 YR 7/6 (reddish yellow)

- Carbonate dominant

- Trace of volcanic rock fragments

g) Photograph the sediment sample with a label, scale and Munsell colour chart_ [Recommended]._

h) Double bag the sample. Label clearly on the surface of the bags, as well as on aluminium tags or waterproof paper placed between the bags. Refrigerate.

Biogeochemistry (chlorophyll-a, organic matter content, redox)

These geochemical analyses are based on the assumption that the sediment surface is relatively intact and the surface sediments can be identified. If this is not the case, it is recommended only organic matter content is assessed, with information on sediment mixing recorded in the comments section of the metadata sheets (Table 9.2). The following procedures are to be used to obtain geochemical samples for quantification of commonly analysed metrics related to chlorophyll-_a_ (Danovaro 2010), organic matter content (Heiri et al. 2001, Wang et al. 2011), and redox (Danovaro 2010, Edgar et al. 2010). For all biogeochemical samples, record the geochemical samples taken on a station form with all available metadata (Table 9.2).

Chlorophyll-_a _& phaeophytin

a) Using a spatula or spoon, scrape the surface sediment to a maximum depth of 2 cm. Collect ~ 100 g wet sediment (1-2 tablespoons).

b) Remove any visible living or soft-bodied organisms for biological steps below, but retain shell gravel.

c) Place a sub-sample of wet sediment into a 50 mL plastic vial for chl-_a_ analysis. Chl-_a_ degrades in sunlight so this step should be performed quickly and out of direct sunlight if possible.

d) Wrap in foil and store frozen at -20°C in the dark until post-survey analysis of chl-_a_. Ensure sufficient head-space in the vial or bag to allow for the expansion of sample when frozen. Note that analysis should be performed within 4 weeks of collection, although use of ultra-cold freezers extends storage times.

Organic matter content

e) Place another sub-sample of wet sediment into a 50 mL plastic vial or small zip-lock bag for post-survey analysis of total organic carbon.

f) Homogenise this sample, and store frozen at -20°C until analysis of organic matter content, generally within 3 months of collection. If liquid nitrogen is available, samples should be snap frozen and stored in a dewar following appropriate protocols.

Redox

g) Use a suitable redox probe consisting of a portable pH/Eh meter, redox electrode (with shaft >15 cm long, preferably as thin as possible, with Platinum indicator electrode) and a reference electrode (double junction silver/silver chloride).

h) Use Zobell’s solution as a reference to calibrate the redox electrode before each redox profile, recording the redox measurement of the solution. The solution (0.003M potassium ferricyanide, 0.003M potassium ferrocyanide, and 0.1M potassium chloride) has an Eh value of +430 mV at 25°C.

i) Carefully insert the redox electrode into the intact sediment surface as soon as possible after collection at depth intervals of 1 cm from the surface to 10-20 cm (depending on depth of sediment).

j) Record the Eh readings (in mV) when the meter readings stabilise (for a minimum of 5 seconds) at each depth.

This method provides a rough indication of the levels of oxygen in the substrate. This information is crucial to assess the interstitial conditions of the sediment as affected by burrowing organisms or anthropogenic factors. Measured in millivolt, often reported as Eh (hydrogen standard electrode) the redox potential has a low-definition significance because of the multi-factors interacting in producing it, and as such is semi-quantitative. Generally positive values are associated with well-oxygenated sediments, whereas highly negative values (<-200 mV) are typical of suboxic or anoxic conditions (Danovaro 2010).

To convert to redox potential and ensure quantitative outputs for comparability between studies, measurements must be calibrated on the Zobell’s measurement, i.e. add the difference to each reading in the profile (difference = std reading at 25°C – field Zobell’s measurement) to standardise measurements for local conditions (e.g. temperature). This must then be standardised based on the standard hydrogen electrode which gives the potential.

Biology (infauna and macrofauna)

a) After supernatant water has been passed through a sieve and sedimentology and geochemistry steps have been performed (< 5 tablespoons of sediment removed, see above), transfer the remaining sample from the grab or corer to an elutriating bin. If additional survey objectives require data on sediment depth (see Pre-Survey Preparations), each sediment layer should be processed in a separate bin.

b) Weigh the whole sample using an onboard scale. Record in metadata sheet (Table 9.3).

c) Rinse the grab or corer thoroughly to avoid contaminating the next sample collected.

d) Elutriate 1 the sample by running moderately flowing seawater into the elutriating bin and gently agitating the sediment to release light-bodied animals into the water. The water should flow from the bin through an outlet under which the sieve is placed (next step). To avoid damage to animals during elutriation, avoid directing water from the deck hose at the sieve, separate fragile visible animals, and remove rocks and shells (these can be saved as part of the heavy fraction if desired, Step 12). Elutriation should be performed until water runs clear, ideally the same amount of time among all sample sites. For coarse-grained sediments, this may only be ~5 minutes, but for deep-sea ooze this may be far longer due to stickiness of the sediment which makes elutriating a challenge.

Fine sediments may require two steps here: semi-elutriation which often retains clods of fine sediment on the sieve, followed by puddling in which a full sieve is immersed in seawater and vertically agitated to further remove fine sediment (CEFAS 2002). This 2-stage option also accounts for shelled molluscs and other heavy-bodied organisms often missed by elutriation. Regardless, the main goal in this step is to ensure that all animals are separated intact from as much of the sediment as possible.

An alternative to elutriation is stacked sieving. This can provide immediate data related to invertebrate size distribution and biomass (Edgar 1990), although sieving is not ideal in coarse-grained sediments where a large fraction is retained on the sieve and subsequently require much time to sort organisms from the sediment. If a researcher elects this option, stack larger sieves (e.g. 1000 µm) on top of smaller ones (e.g. 500 µm), add small amounts of sample to the top sieve, and gently flush through with seawater. Skip to Step 12.

e) Retain macrofauna by allowing water to flow onto a 500 µm sieve. This size was chosen, as it has already been used in AMPs (Nichol et al. 2013, Przeslawski et al. 2013, Przeslawski et al. 2018) as well as successful international monitoring of soft sediment communities (Frid 2011). It is a compromise between the 1 mm recommended by other protocols (Rumohr 1999) and the time and effort needed to process specimens using 300 µm or smaller. If individual survey objectives require a finer mesh size (e.g. 100 µm or 300 µm) or comparison with datasets from larger mesh size (e.g. 1000 µm), layer the sieves and process samples separately so that the recommended standard of 500 µm is still followed and data are comparable.

f) Sort the heavy fraction by hand, remove any live animals that do not float during elutriation (e.g. molluscs, hermit crabs, animals attached to rocks), and place them in the sample container.

g) Material retained on the sieve should be flushed off using seawater in a squirt bottle directed from the underside of the sieve into a funnel and sample container. It is important to minimize the amount of water used in this step to ensure adequate preservative concentration. If a large amount of seawater is used for flushing, the sample can be sieved and flushed again. Alternatively, a puddling bin can be used to concentrate the sample into one small area of the sieve for flushing into the sample container (CEFAS 2002).

h) Preserve the elutriated and heavy fraction specimens in a sample container according to the methods decided in ‘Pre-survey Planning’. If there is a large volume of material, use multiple sample containers to ensure enough preservative in each container. Consider museum requirements for sample preservation, and also see Rees (2009) and Schiaparelli et al. (2016) for a comprehensive description of fixatives and preservatives used for marine invertebrates. Larger organisms may be preserved separately (e.g. polychaetes may be relaxed in MgCl2 and fixed in formalin).

i) Place a solvent-hardy label in each sample container with sample and station number, date, location and vessel/collector. This information is essential for quality control in processing and archiving of specimens. It is not sufficient to label only the outside of the container, as this can easily rub off. See Box 15.6 in Schiaparelli et al. (2016) for suitable label characteristics.

j) Place the sample container in a large sealable container (i.e. lidded drum) double-lined with a durable plastic bag with other samples preserved using the same chemicals (e.g. ethanol). Label the drum with survey details and the type of chemical fixative/preservative inside. Since samples from the same grab may end up in different drums due to different preservatives, it is imperative to have a good record-keeping system.

k) After placing samples within the inner bag of the drum, back fill between the bags with an appropriate amount of spill kit (e.g. vermiculite or absorbent kitty litter). In this way the contained specimens are compliant with handling (triple bagged) for road transport of Dangerous Goods. [Recommended]

l) Store large drums onboard in an approved storage area for hazardous chemicals.

1 Elutriation is a process that uses water to float less dense animals away from the sediment. It is a useful technique to separate fauna such as crustaceans and polychaetes but not suitable for gastropods and bivalves.